Economic growth is expected to decline in 2020, affected by the ongoing shock.

The Coronavirus Outbreak and Government Actions to Prevent Transmission

Suriname confirmed its first imported COVID-19 case on March 13, 2020. As of March 26, the authorities had confirmed a total of eight cases with 320 persons in quarantine. Up until now, all cases have been classified as imported.

The authorities acted swiftly to contain further importation of the virus and prevent community spread by imposing travel restrictions and implementing a number of social distancing measures. Measures implemented to date include the indefinite closure of all borders (land, sea, and air) and measures to facilitate the return of foreigners to their country of origin and retrieve Surinamese nationals in foreign countries. The authorities also limited social gatherings, closed all schools and universities, and restricted in-restaurant and bar dining services (take-out services are allowed). Communication of COVID-19 developments to the public occurs via a daily press conference as well as through a dedicated website and press briefings.

Economic Growth Prospects: Then and Now

Economic growth is expected to decline in 2020, affected by the ongoing shock. As discussed in the December 2020 Caribbean Quarterly Bulletin, the country’s economic growth was expected to continue to improve over the medium term, with real GDP growth estimated to reach 2.5 percent in 2020. However, recent developments now cast doubt on that assumption. Lower growth at best or an economic contraction at least similar to the 2015 decline (-5.6 percent) is expected for 2020.

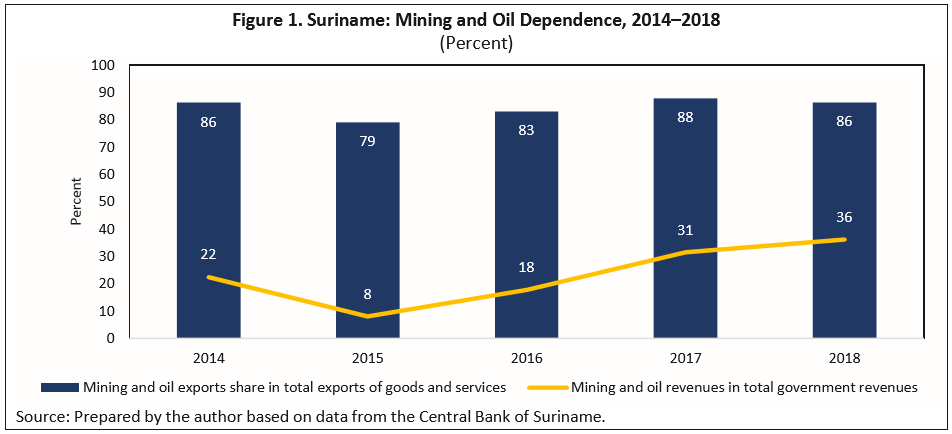

Transmission channels are varied and affect all sectors of the economy, either directly or indirectly. The main transmission channel for Suriname will be commodity prices (gold and oil), given the country’s high commodity dependence (Figure 1). The International Monetary Fund (IMF) baseline assumptions for crude oil and gold prices to support economic growth of 2.5 percent in 2020 were US$57.9 per barrel and US$1531 per troy ounce, respectively. However, due to COVID-19-related supply and demand shocks and tensions between Russia and Saudi Arabia, crude oil prices plummeted by 60 percent in March 2020 (compared to IMF baseline assumptions) (IMF 2019c). Gold prices have been fluctuating, with a marginal difference around the IMF baseline assumption.1 The ongoing commodity price shock will have negative effects on growth, and could further weaken Suriname’s fiscal and external positions.

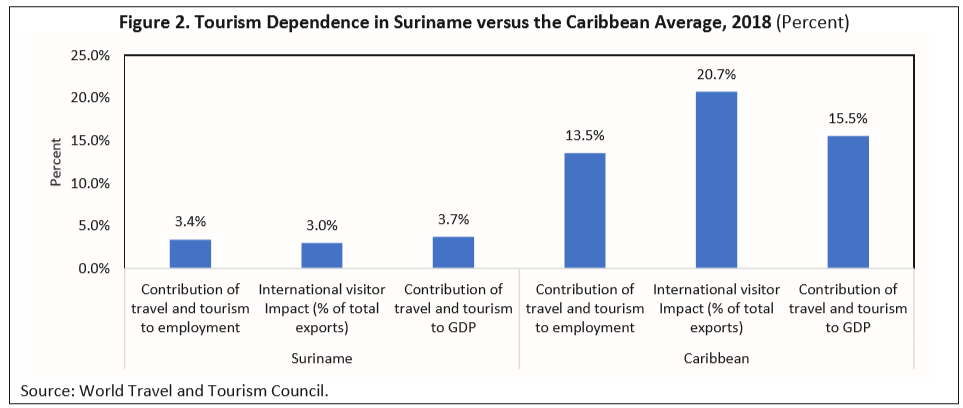

Second-round effects would occur through the impact of social distancing measures and internal and international travel restrictions. The necessary restrictions associated with social distancing globally and within Suriname could have large adverse effects on domestic economic activity, depending on how long they remain in effect. The “face-to-face” industries such as entertainment, restaurants, bars, retail, transportation, and home care services are expected to be affected the most during this period. Moreover, new investments are expected to be postponed and ongoing infrastructure projects could suffer delays in implementation, affecting economic activity in the construction sector. Although the tourism sector in Suriname is relatively small (Figure 2), there could be large effects on businesses and households that depend on the travel and tourism value chain (e.g., hotels, restaurants, transportation and tour operators).

Government Policy Response

The ongoing shock is having an unprecedented impact in advanced and emerging economies, with large spillovers expected for small open economies like Suriname. COVID-19 is causing a trade-off between public health and economic health as many countries temporarily close non-essential services and businesses and ask employees to stay at home. In that context, it would require an immense coordinated policy response—fiscal, monetary, and social policies—to first “flatten the curve” of COVID-19 and then implement a multisectoral policy response to address the resulting economic challenges. In Suriname, macroeconomic policy responses are being considered, but current policy constraints will likely cause the trade-off mentioned above between public health and economic health. Suriname’s policy options and constraints in terms of fiscal policy, monetary policy, and social policy and support for businesses are outlined below.

Fiscal policy: Ongoing policy discussions are focused on ensuring that the distribution of basic supplies and crucial government services and utilities continues during the COVID-19 crisis period. The authorities are also looking at measures to support the business sector. However, fiscal policy response is constrained by challenging macroeconomic conditions and a precarious fiscal position. The ongoing shock is likely to worsen the fiscal accounts through a decline in revenues (mostly oil) and also reduced tax receipts. Nevertheless, a large fiscal effort is needed to mitigate the effects of COVID-19 and support households and businesses. The trade-off here is worsening economic conditions in the short term to preserve public health. In that regard, it would be important to increase budget allocations to address the COVID-19 crisis by reorienting planned expenditure in the short run and seeking low-cost financing in order to (1) provide cash and in-kind transfers, especially for vulnerable people who are likely to lose their jobs and income during the crisis period, (2) use and strengthen the effectiveness of the social safety net to respond to the ongoing shock, and (3) pursue sector policies to ensure business survival post COVID-19, especially in the transportation, tourism, and hotels sectors, perhaps in the form of tax relief and/or working with banks to offer deferred payment options. Post-crisis policies would need to focus on restoring fiscal stability by strengthening the fiscal framework (see IMF 2019c for specific measures).

Monetary policy: A monetary policy response to the ongoing crisis is challenged by relatively high levels of nonperforming loans estimated at 12 percent of total gross loans as of the second quarter of 2018. Moreover, a de facto peg to the U.S. dollar, with a high and increasing trend in the parallel market rate (the current parallel market premium is over 70 percent),2 along with relatively low and falling international reserves, also constrain the policy response. Lowering reserve requirements could be an option to increase liquidity, but this (together with the required fiscal effort) could worsen the abovementioned challenges. Nevertheless, if the ongoing crisis deepens, the authorities would have to carefully weigh the trade-offs between public health and economic health.

Social policy and support for businesses: The authorities have announced social support measures for vulnerable groups during the period. These include enhanced supervision of price speculation and advising companies not to dismiss employees during the crisis. Commercial banks have also increased withdrawal limits at automated teller machines and strongly encouraged the use of online banking. Finabank (a privately-owned commercial bank) also announced that its customers would be eligible for deferred payment on their obligations if their business operations are affected by the COVID-19 virus.

Footnotes:

1 It is expected that gold prices could further improve in 2020, which could help offset declines in other areas.

2 A recent amendment to the Currency Control and Transaction Offices Control Act now stipulates that only the official rate of the Central Bank of Suriname should be used in all domestic transactions. The exchange houses, banks, and the business sector are currently challenging key elements of the amended law.