This pandemic has generated an unprecedented wave of economic shocks for the Caribbean. We are working with governments in the region to respond quickly and deploy all available resources.

Caribbean economies in the time of the coronavirus

Introduction

This special edition of the Caribbean Quarterly Bulletin focuses on the evolving economic and human consequences of the ongoing COVID-19 outbreak for countries in the Caribbean region.1 Our team of economists based in countries across the region has been working to assess the situation and advise senior management of the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) and stakeholders from member countries about the potential implications of the shock, as well as policy responses best suited to mitigate its effects. First and foremost, the focus is on reducing the human impact of the crisis. Lives are at stake, but that said, so are livelihoods. As a result, it is important to try to understand the economic forces at work in order to think through appropriate policy responses.

From an economic perspective, the analysis identifies two broad challenges:

-

The domestic economic impact of social distancing measures. As necessary as these measures are, it is extremely difficult to foresee the direct economic impact from lost revenue, employment, and productivity in the “face-to-face” service sector.2 Naturally that impact will depend upon the duration of these measures. It will also depend upon complementary actions in the public health sector and other areas to “flatten the curve” and avoid the exponential growth of cases.

-

External shocks from a combination of supply and demand factors. First, tourism is arguably the sector most affected globally by the coronavirus. Other sectors clearly are experiencing stress in supply chains, but the global tourism industry is experiencing an unprecedented shock. Even if the travel restrictions can be removed safely, if the world is in recession, tourism will continue to be affected. Second, a combination of factors is contributing to low oil and gas prices, geopolitical on the supply side, combined with the sharp slowdown in large economies, on the demand side. Third, gold is a leading export for Guyana and Suriname. The price of gold tends to increase during periods of global financial stress, but it also becomes more volatile. On the side of imports, disruptions in transport and global supply chains might limit access to key basic goods, including food, and both intermediate and capital goods required for production and investment. Finally, risk aversion and financial turbulence make it more difficult for Caribbean countries to access external finance at a reasonable cost.

In brief, on the domestic front, there are many challenges posed by social distancing that demand a policy response to ameliorate the impact. On the external front, the story is primarily one of tourism and commodities, and the evolution of these sectors will shape macroeconomic policy over the coming months. Policies will also be influenced by the incipient global recession.

This special edition of the Quarterly Bulletin is not intended as a definitive analysis of this fast-moving situation. Rather, it outlines the key transmission channels for the ongoing crisis and the broad policy options facing policymakers. One area highlighted in considerable detail is tourism, though there is also a focus on several other areas, including a variety of macroeconomic modeling exercises and attempts to assess the effects of the crisis at the household level. We will be providing more detailed analysis in forthcoming publications over the coming weeks and months, as this urgent work program progresses.

Job 1: Stopping the Spread of the Coronavirus

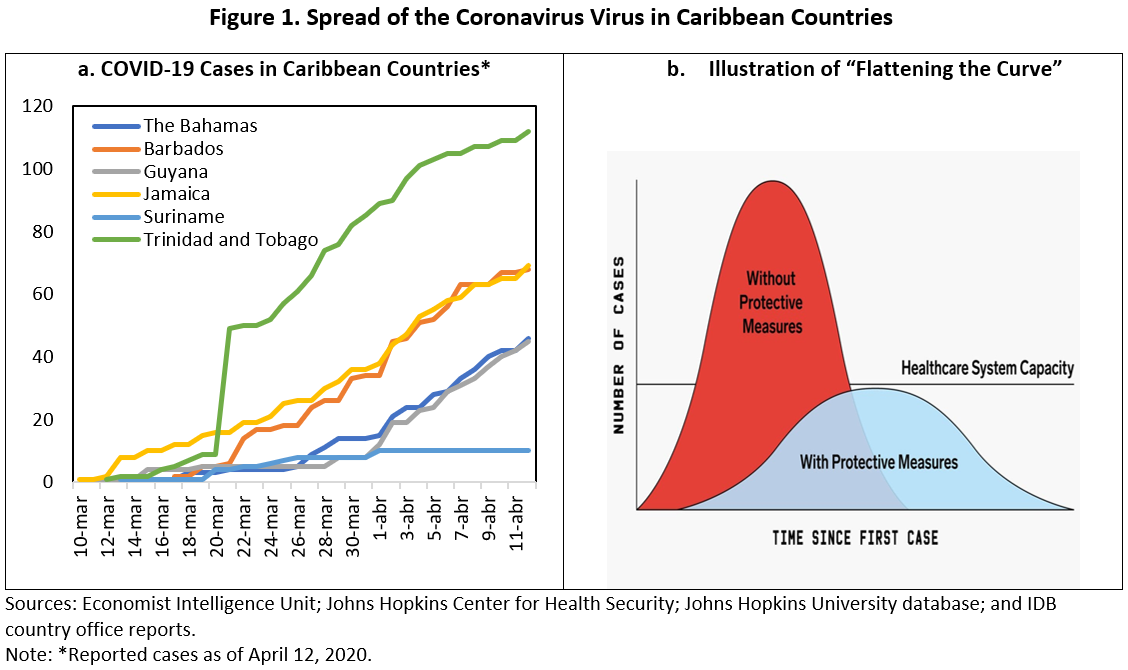

As of April 12, 350 cases had been reported in the six Caribbean countries examined here (Figure 1, panel 1). The domestic economic impact directly related to the disease is very difficult to predict, and obviously it depends on the direct measures under way in each country to combat the spread. Face-to-face service sectors are experiencing a sharp decline as businesses are ordered closed and consumers are required to stay at home. Both supply and demand are effectively shut down. In tourism-dependent economies, this exacerbates the decline in tourism arrivals, while in commodity-dependent economies, this amplifies the impact of the decline of commodity prices on government revenues. Creative solutions through technology can help, ranging from safe prepared food delivery to virtual legal advice, online education, and a host of other possibilities. Still, the short-term impact is severe.

Social distancing measures are obviously necessary to save lives, which is the most important priority for governments all around the world. From an economic perspective, people represent a valuable economic asset. If these economies can emerge from the immediate crisis with their human capital stock intact, then long-term economic growth will still be viable. This human capital stock has an economic value that is multiples of the value of annual GDP.

The key to saving lives and the associated human capital they bring to economies is to “flatten the curve” in terms of avoiding an exponential infection rate, which could overwhelm national health systems (Figure 1, panel b). The region is still in the early stages of the virus, and the numbers are still small, even relative to the small populations of the Caribbean countries, but the curve is not flattening yet.

External Shocks: A Tale of Tourism and Commodities

As noted in the introduction, the impact of this crisis for individual economies will differ depending on the structure of the economy (e.g., dependence on tourism vs. commodity exporter) and the transmission channels through which the shock propagates. Key direct external channels include physical and financial linkages with the rest of the world. In general, the two most significant conduits for shock transmission will include international trade (including goods and services trade) and financial flows. For the Caribbean countries, both channels are significant, particularly the trade channel, which includes the two most important sectors for Caribbean economies—tourism and commodities exports.

Shocks to Tourism Flows

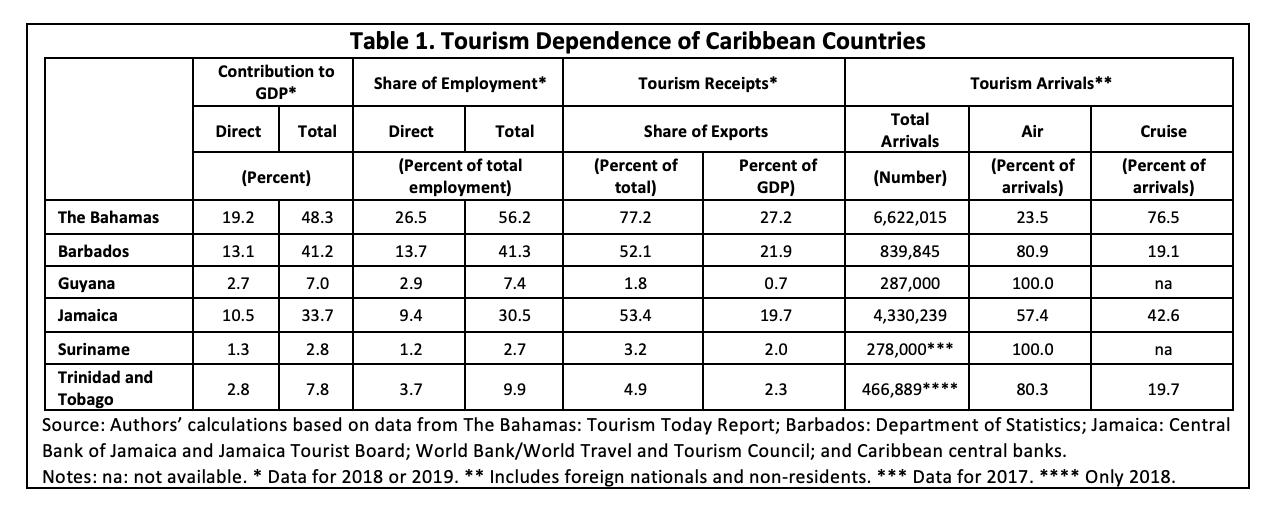

Some Caribbean economies are among the most tourism-dependent in the world. Tourism accounts for between 11 and 19 percent of direct output (GDP), and between 34 and 48 percent of total GDP in The Bahamas, Barbados, and Jamaica (Table 1). Tourism flows are also responsible for similarly large shares of direct and overall national employment, with all three countries ranking in the top 20 globally on both measures. Related receipts are also equal to over half of total exports of goods and services for these three countries. Cruise ship tourism—already heavily affected by the crisis—also represents a very large proportion of total tourist arrivals for both The Bahamas and Jamaica—77 and 42 percent, respectively. In the other Caribbean countries, tourism has a much smaller, but still not insignificant, role in their respective economies.

Historical Shocks to the Tourism Sector in Caribbean Countries

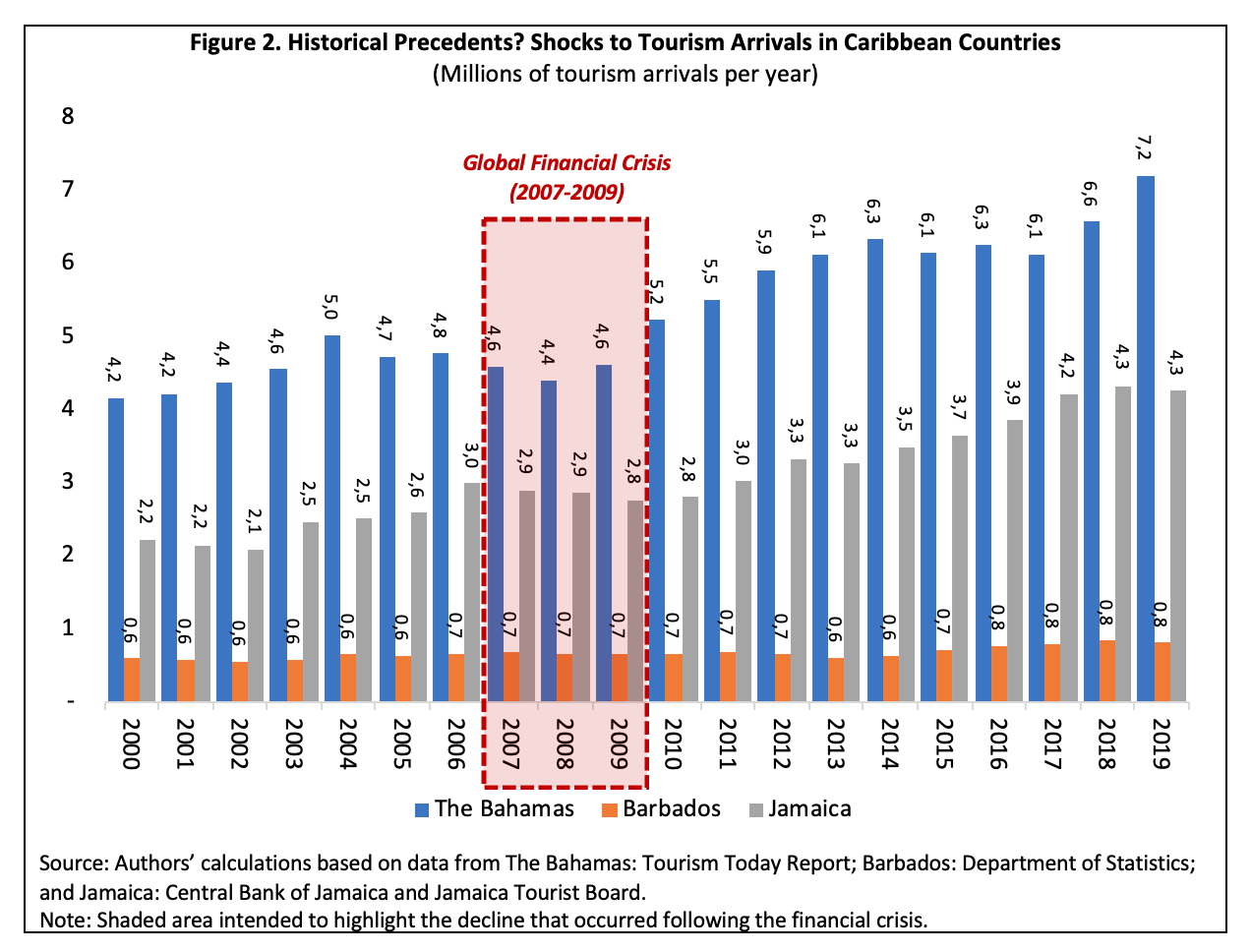

The significance of the sector for tourism-dependent economies is clear. The potential implications of the current crisis are, however, more difficult to determine. As a first step, we created a new database for both air and cruise passenger arrivals going back as far as January 2000. Based on these data, we calculate that annual tourism arrivals increased appreciably from 2000 through 2019 for The Bahamas, Barbados, and Jamaica—by 73 percent, 37 percent, and 91 percent, respectively.

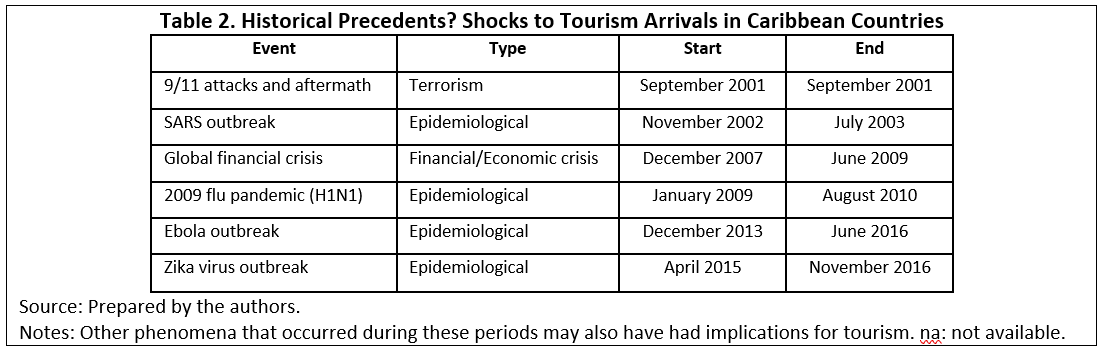

In considering the potential implications of the COVID-19 crisis on the Caribbean economies, it is important to determine whether we can look to historical precedents as examples (Table 2). There have been several shocks over the past two decades that are likely to have affected either global demand for tourism, or the ability of passengers to reach the region. In this context, we identified six episodes since 2000 worthy of closer scrutiny: (1) the 9/11 attacks (September 2001); (2) the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) outbreak (November 2002 to July 2003); (3) the global financial crisis (December 2007 to June 2009); (4) the 2009 flu pandemic (H1N1) (January 2009 to August 2010); (5) the Ebola outbreak (December 2013 to June 2016); and (6) the Zika outbreak (April 2015 to November 2016). While these six shock episodes differ in their nature, origin, and duration, they all had some effect on global travel and tourism flows. It is also true that in some cases, these episodes unfolded over relatively long periods—in some cases over several years—suggesting that other unrelated factors may also have had some influence on tourism arrivals to Caribbean countries during the same period, including economic issues, natural phenomena, and/or geopolitical factors.

A review of these shock episodes relative to arrivals reveals that an appreciable decline in tourism for all three tourism-dependent economies in the region simultaneously was only observed during one of these six shock horizons—the global financial crisis.3 After year-on-year growth in tourism for The Bahamas, Barbados, and Jamaica in 2006, all three countries saw reductions in arrivals at some point from 2007 through 2009 (Figure 2). These declines were matched by contractions in GDP for each of the countries.

In terms of how the financial crisis and other periods of decline over the past two decades compare to the current situation, it is difficult to draw parallels. A review of tourism arrivals (both air and cruise arrivals) between 2000 and 2019 for all three Caribbean countries reveals that the largest single-year reduction was about 6 percent relative to the previous year. The near-complete shutdown of both passenger air travel and cruise ship activity beginning in March 2020 would imply a much larger shock to tourism arrivals and related receipts for 2020. In this context, we conclude that there is no precedent—at least in recent decades—for the current shock to tourism in the Caribbean region.

Shock Scenarios and Simulations

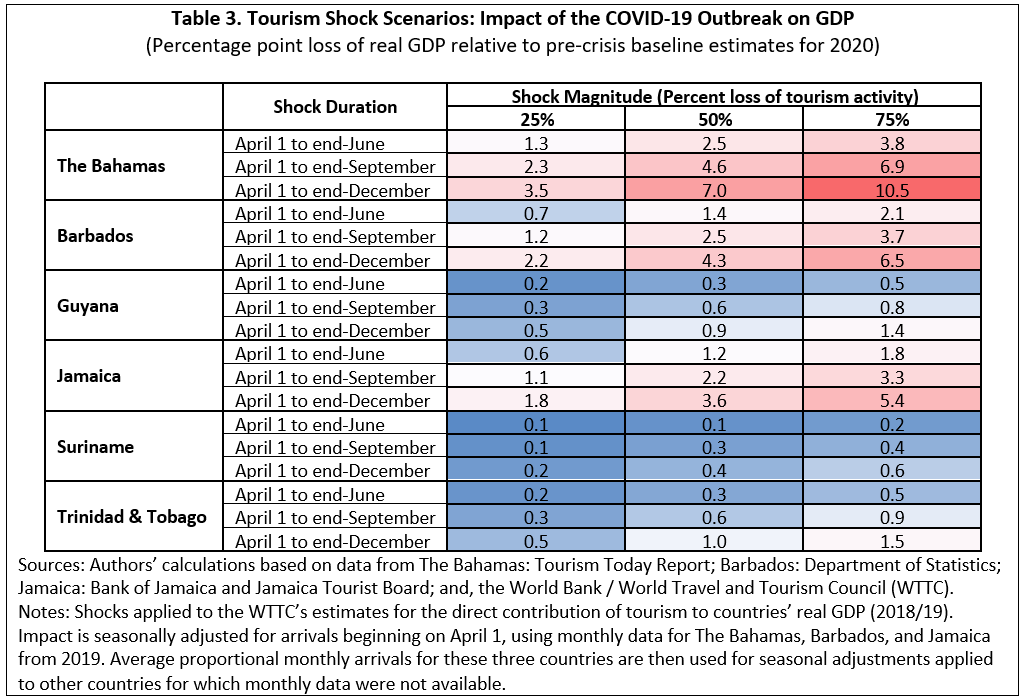

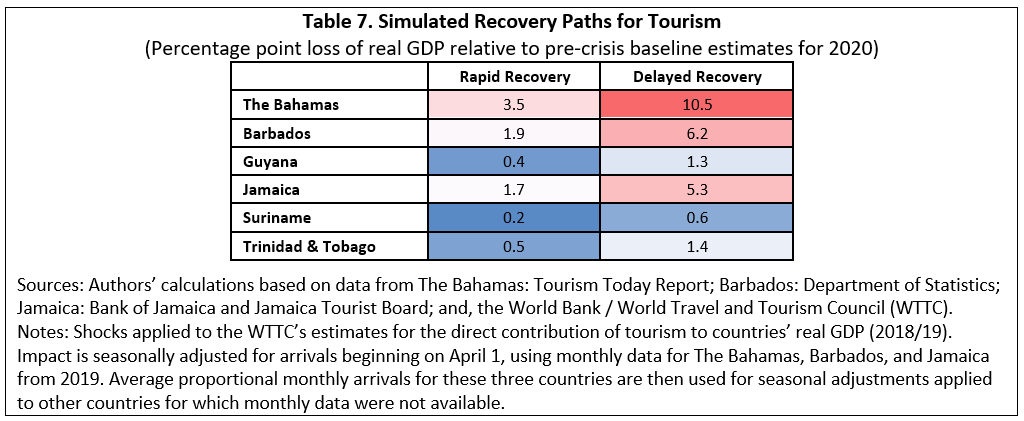

Given that the shock to tourism driven by the COVID-19 outbreak is without precedent in recent history, developing scenarios and simulations can provide some indications of potential implications. Using data discussed above, we have estimated a range of shocks to the direct contributions of tourism to real GDP for each Caribbean country (Table 3). We simulate the possible impact on output of three shock magnitudes (i.e., a reduction of tourism activity by 25, 50, and 75 percent) over three time horizons beginning on April 1, 2020 (i.e., through end-June 2020, end-September 2020, and end-December 2020). The simulations take into account historical seasonal arrival patterns for each of the shock horizons. This is important to the exercise given the large seasonal fluctuations in tourist arrivals to the region, with increases of much as 200 percent between high seasons (generally October to April) and the lower-volume period. In this context, should the crisis remain acute past September 2020, we would expect the effects to be considerably more severe.

The scenarios do not, however, take into account shocks to other sectors (e.g., merchandise or commodities trade4), second-round effects, or possible offsetting implications of policy measures (e.g., economic stimulus). Similarly, we apply the shock to the World Trade and Tourism Council’s (WTTC) estimated historical direct contributions of tourism to real GDP, which does not take into account the nonlinear properties of such a shock, particularly the fact that shorter duration shocks are likely to have less severe implications for businesses (e.g., hotels, restaurants, service providers, etc.) than a prolonged crisis. For example, a short-lived shock may not require broad-based lay-offs or extended closures, which could lead to significant financial difficulties for many affected enterprises, whereas a prolonged shock could force businesses to make more severe adjustments.

While the shock scenarios outlined in Table 3 are incomplete for the reasons mentioned above, they do highlight that the impacts of a short-lived crisis would be considerably less damaging than one that extends through the peak season beginning later in the year—particularly for countries with large seasonal variations. In this context, results of our simulation of a high-impact scenario of a 75 percent reduction in tourism arrivals over the last three quarters of the year suggests that real output could fall relative to the pre-crisis baseline expectation by over 10 percentage points of real GDP in the case of The Bahamas, and by appreciable magnitudes also for Barbados and Jamaica. Note that applying these same shock scenarios to the WTTC’s estimates for the total contribution of tourism to each country’s economic output (see Table 1, above) would result in larger impacts.5 Countries that are less dependent on tourism would be less affected across the range of scenarios, though other channels not simulated here could also have large effects.

Shocks to Commodity-Dependent Economies

The three most significant commodities in the region are oil and natural gas for Trinidad and Tobago and now Guyana, and gold for Suriname and Guyana. The downward trajectory in oil and gas prices will hurt those commodity exporters, but it can help commodity importers—providing some relief to the countries negatively affected by the tourism crisis (Figure 3). Gold is highly volatile, but there is a tendency for its price to remain strong during times of financial turbulence. The evolution of these commodity prices will have an important impact on the external accounts of the Caribbean countries. Aluminum prices are also on a downward trajectory, which is relevant for Jamaica as it represents the largest merchandise export.

It should be noted that on the oil and gas front, there are various factors at work. Oil prices are currently under pressure for both demand and supply factors. The incipient global downturn is resulting in lower energy consumption in the largest economies. At the same time, geopolitical issues have led to a lack of agreement on production targets between OPEC countries and the Russian Federation. In particular, a sharp expansion in Saudi oil production has contributed to falling oil prices as the COVID-19 situation has unfolded.

How some of these price shocks affect the commodity-exporting Caribbean economies is discussed further in this issue in the section entitled “Putting It All Together: Economic Growth in 2020.”

Finance

As noted above, another key shock transmission channel relates to financial flows from abroad. These flows can take the form of investments (e.g., portfolio or direct investment), other financing flows (e.g., debt), or transfers (e.g., official transfers or private remittances). The impact of the crisis on both foreign and domestic economic performance and capital markets will have implications for these flows.

For example, if local businesses see earnings fall and prospects deteriorate, their financial viability and creditworthiness will ultimately affect the cost and volume of financing and investment available from abroad. Similarly, increasing risk aversion on the part of would-be foreign investors is also likely to translate into costs and other implications for funding. Finally, actual or anticipated exchange rate movements linked to the COVID-19 crisis could also affect the willingness of foreign investors and financial entities to invest. At this early stage, the above-mentioned effects of the crisis on financial flows are difficult to determine. To date, countries with flexible exchange rates in the region have not undergone any significant nominal adjustments, and data on portfolio flows since the crisis moved into a more acute phase not yet widely available.

Finally, domestic financial sources can be a substitute for external finance for government and firms in adjusting to the economic shock. This obviously depends upon the depth and stability of domestic financial systems. Domestic finance does not, however, attend to foreign currency requirements to finance the balance of payments. Each of these issues is addressed briefly below.

Government Finance

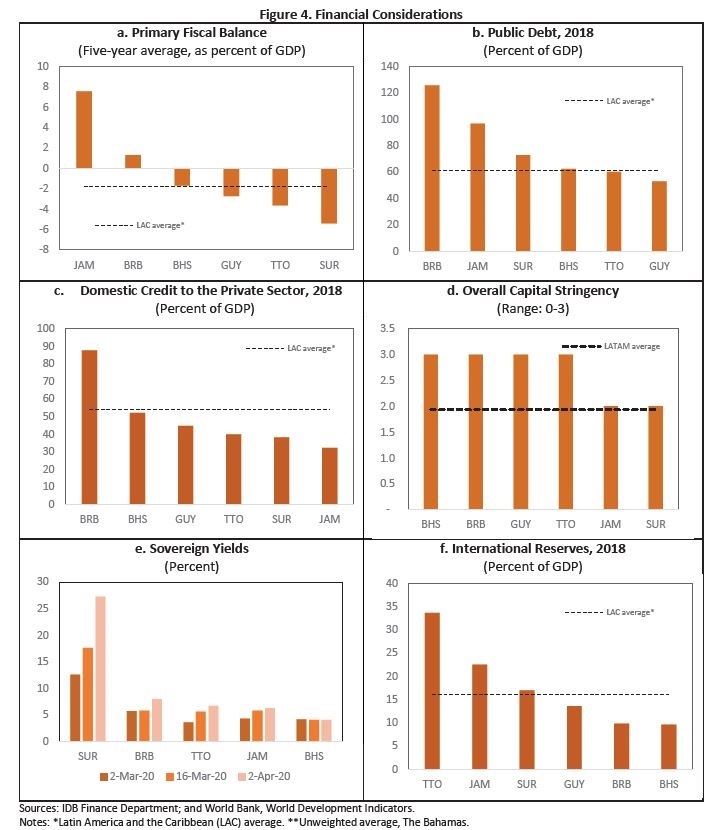

The main problem for government finance is that fiscal buffers are limited in most Caribbean countries. Countries like The Bahamas, Guyana, Suriname, and Trinidad and Tobago have experienced a rise in the public-debt-to-GDP ratio in recent years, as public deficits have persisted (Figure 4, panel a). Meanwhile, Barbados and, especially, Jamaica have reduced their public-debt-to- GDP levels, but debt burdens remain extremely high by regional and international standards (Figure 4, panel b). Trinidad and Tobago is a special case, in that it has a Heritage and Stabilization Fund (HSF), with assets of about 28 percent of GDP. As the name implies, the HSF serves a dual role: saving oil wealth for future generations while also providing a source of funding for short-term stabilization. Other Caribbean countries do not have access to such resources; however, Guyana’s situation is changing rapidly as oil revenues start to be received.

Private Sector Finance

Firms also need finance to survive the shock, and if external finance dries up, firms can turn to domestic sources. That depends, though, upon the degree of development of the domestic financial system. One summary indicator is the extent of domestic credit to the private sector as a share of GDP. Panel c of Figure 4 shows that financial sector development varies substantially across Caribbean countries. In some cases, the low share of domestic credit to the private sector is partially due to the still large share of banking sector assets held as government debt. In other cases, it may be due to regulatory and institutional failings that inhibit the growth of the financial system.7

Extending creditexcessively can be a risk factor. However, in general terms, Caribbean banks are well capitalized. Panel d of Figure 4 presents a summary measure of this dimension. The indicator measures whether the capital requirement reflects certain risk elements and deducts certain market value losses from capital before minimum capital adequacy is determined. Larger values of this index of bank capital regulation indicate more stringent capital regulation. Countries with higher levels of capital stringency have adopted at least the Basel II standards and cover credit and market risks in their current minimum regulatory capital requirements.7 The results suggest that The Bahamas, Barbados, Guyana, and Trinidad and Tobago have higher levels of capital stringency compared to Jamaica and Suriname. Overall, Caribbean countries have higher levels of capital stringency compared to the average for Latin American countries (LATAM).

Balance of Payments Financing

All six countries examined in this issue are open economies, that depend crucially on imports for consumption, intermediate inputs, and for capital goods. Of particular concern is the dependence on imported food. As noted in a report by the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO 2015, Executive Summary p. x): “Almost all CARICOM countries import more than 60 percent of the food they consume, with half of them importing more than 80 percent of the food they consume.”

Foreign currency is needed to purchase imports and to service external liabilities. The previous section presented the scenarios for the likely negative shocks to export earnings from tourism services. In brief, the tourism shock this year could imply one of the largest declines in foreign currency earnings ever experienced by the tourism-dependent economies. Balance of payments financing could become critical.

In addition, several of the Caribbean countries receive foreign currency through migrant remittances (Box 1). These could be at risk as unemployment rises in migrant host countries—predominantly, the United States, United Kingdom, Canada, and the Netherlands (for the case of Suriname).

One indicator that suggests that access to external finance is tightening is the fact that bond yields have increased on secondary markets for the Caribbean countries (Figure 4, panel e), with the exception of The Bahamas. As in the case of government finance, financial buffers vary across the Caribbean countries (Figure 4, panel f), with relatively high levels of international reserves in Trinidad and Tobago and Jamaica, but less so in The Bahamas and Barbados.

Box 1. Remittances to the Caribbean

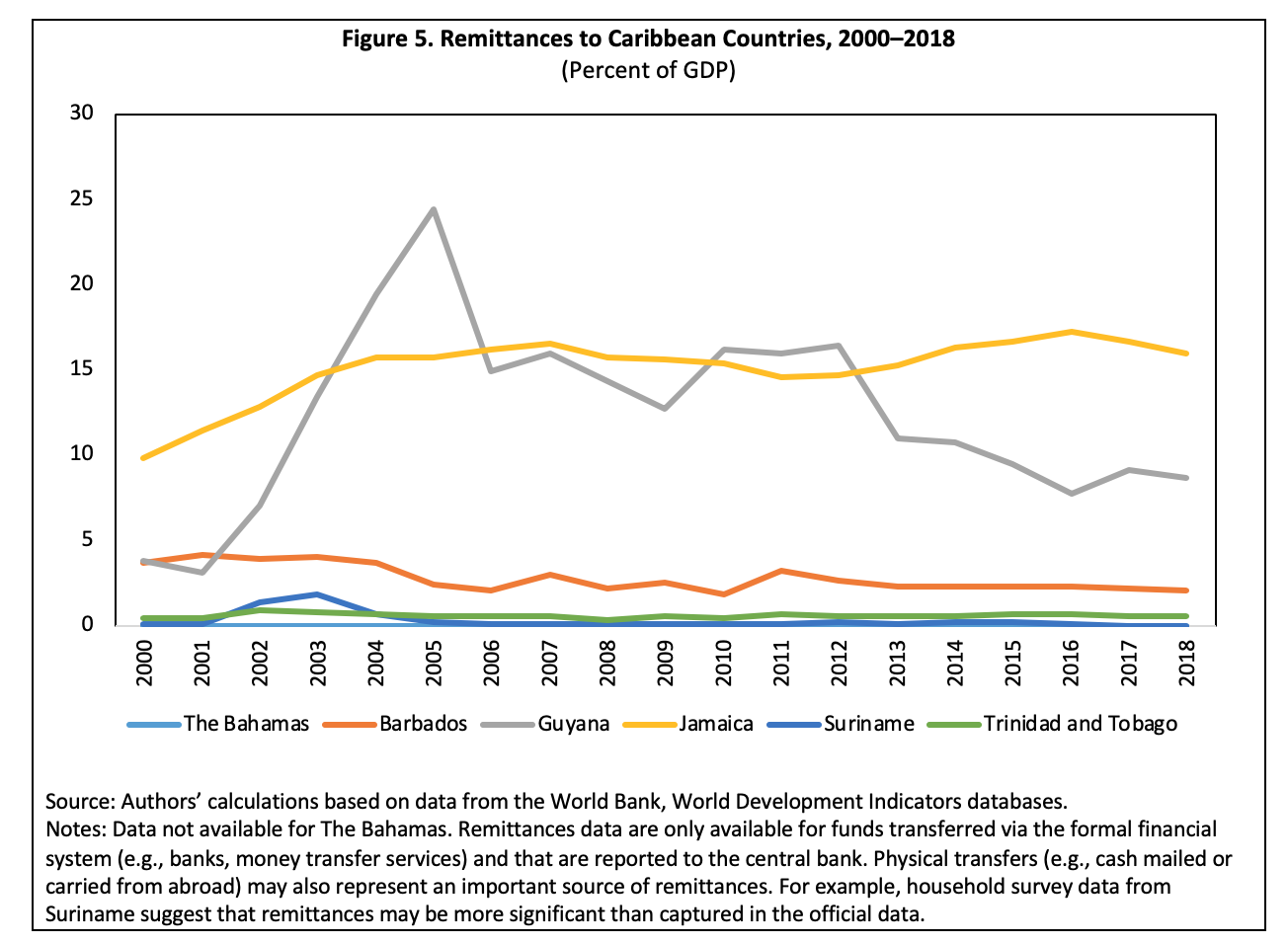

One key financial channel given its significance for several Caribbean countries is remittances. Private remittances from abroad have long served as important sources of foreign exchange for countries like Jamaica, Guyana, and to a lesser degree Trinidad and Tobago, Barbados, and Suriname. These remittances have grown considerably over the past two decades, reaching as much as 15 percent of GDP for both Jamaica and Guyana over that period (Figure 5). Note that these data also underestimate the true volume of remittances flowing into the region, as what we are able to capture reflects funds flowing into countries from abroad via licensed financial institutions such as banks, wire transfer companies, etc. It is likely that a substantial volume of these funds are sent via other unregistered means (e.g., the mail, physically transported over the border, etc.).

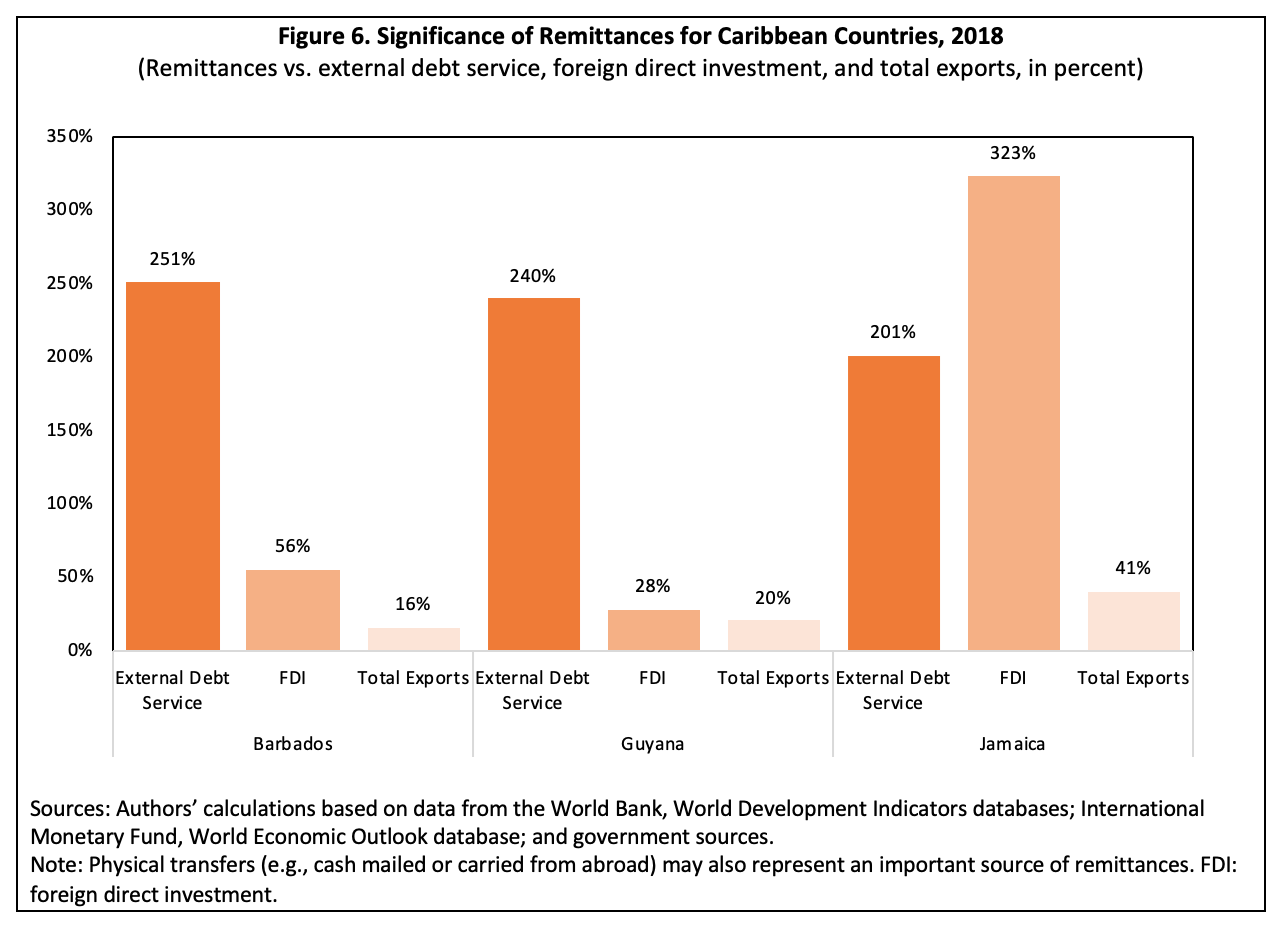

Another important role of remittances for Caribbean economies is as a source of financing for the balance of payments (e.g., imports from and debt repayments to other countries), which has allowed countries with relatively narrow production bases and limited or volatile export earnings to consume foodstuffs, commodities, manufactured goods, and services from abroad that might not otherwise be financially feasible. In this context, remittances represented the equivalent of between 201 and 251 percent of total external debt service requirements, or the equivalent of between 16 and 41 percent of total export earnings in 2018 for Barbados, Guyana, and Jamaica (Figure 6).

A growing concern today is the fact that the source of remittances to emerging economies—particularly Caribbean economies—tends to be migrants working in lower-skilled sectors and industries in advanced countries that seem most immediately and profoundly affected by the current crisis. While data are not yet publicly available regarding changes to the volume of these flows to Caribbean countries, what is clear is that unemployment claims in the United States, Canada, and other key sources of migrant remittances to the region have seen unprecedented increases in recent days and weeks. These and other shocks related to foreign exchange inflows could have significant ramifications for balance of payments sustainability and exchange rate dynamics, as well as for vulnerable citizens who depend on them most.

Putting It All Together: Economic Growth in 2020

To sum up, the analysis for this special edition of the Caribbean Quarterly Bulletin has employed a variety of techniques to simulate the potential impact of the coronavirus crisis on growth. Projecting actual growth rates for the rest of 2020 is almost impossible, as noted above, but one can do simple simulations that provide information on just how bad the situation could get.

Tourism-Dependent Economies

The approach used for the tourism scenarios presented earlier has been validated by a separate exercise using vector-autoregression techniques that result in a similar range of values. We have also deployed other techniques in other countries, including general equilibrium models for Barbados, with results that will be published in the coming weeks.

At this writing, the tourism sector in Caribbean countries is almost completely shut down. The analysis presented previously suggested that a sustained six-month disruption of tourism, on the order of a 75 percent decline in tourism receipts, would lead to double-digit declines in economic growth for The Bahamas, Barbados, and Jamaica.

In addition to the various scenarios with fixed durations and magnitudes presented earlier, we have also simulated two alternative recovery paths representing possible trajectories for tourism flows to the region: a rapid recovery, and a delayed recovery (Table 7). The rapid recovery scenario envisions a 75 percent reduction of tourism flows relative to 2019 during the second quarter (Q2) of 2020, followed by a recovery to 50 percent in Q3, and a return to 100 percent of the level observed in 2019 for Q4. A delayed recovery scenario envisions a full cessation of tourism across all Caribbean countries during Q2, followed by a 75 percent reduction during Q3, and a 50 percent reduction during Q4. Though all caveats mentioned above remain applicable, these scenarios underscore that a crisis whose apex is reached earlier in the year—that is, before the beginning of the peak season in the fourth quarter—could be considerably less damaging than one that remains acute through the end of the year.

As noted above, one compensating factor for these tourism-dependent economies is that they are oil importers. Savings from lower oil prices would provide fuel cost savings to these economies.

Commodity Exporters

In oil and gas producing economies, the key factor is the commodity price decline. A good example is Guyana. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) projected GDP growth of 86 percent for Guyana in 2020, based on oil production starting in 2020 at a rate of approximately 102,000 barrels/day (bpd). Oil exports were valued at US$2.4 billion, and oil-related government revenue of US$230 million. But this projection assumed an oil price of US$64 per barrel. The WTI oil price was trading at about US$24 per barrel on the afternoon of April 8, 2020. The first of five expected shipments for 2020 was transacted in February at a price of US$55 per barrel. But given current events, what will happen for the rest of the year? One simple simulation with oil at US$20 per barrel leads to economic growth that is half of what was projected by the IMF last fall, with similar effects on government oil-related revenue.

In Trinidad and Tobago, gas production outstrips oil production tenfold in equivalent barrels of oil. Based on December 2019 production (3.4 billion cubic feet per day), gas production in 2020 is estimated at 1.25 trillion cubic feet. For April to December, gas production would amount to 933.3 billion cubic feet. Taking the IMF’s 2020 gas price of US$2.7/mmbtu, the value of gas exports for April-December is estimated at US$2.51 billion. However, assuming a gas price of US$1.8/mmbtu, which is the government’s working assumption, the value of gas exports would drop to US$1.67 billion, corresponding to a 33 percent drop in the value of gas exports. Assuming a gas price of US$1.6/mmbtu, the value of gas exports would drop 40 percent. Natural gas and oil exports together add up to about 18 percent of GDP. The knock-on effects of lost income and potential decline in sector investments could have a large effect on economic growth this year.

Suriname is a net oil importer, but oil sector production still represents an important part of GDP and could be negatively affected in ways similar to Trinidad and Tobago and Guyana. On the external front, the price of gold, Suriname’s largest commodity export, has remained high relative to a couple of years ago, but somewhat below the peaks experienced during the height of the European banking crisis (2012– 2013), and this helps support exports. That said, there are domestic factors surrounding the ongoing crisis, along with political uncertainty, that are negatively affecting the economy in the near term.

Domestic Factors

As noted above, the world is in uncharted territory in terms of the degree of social distancing that is being implemented globally. As mentioned in the introduction, the duration of these actions is difficult to predict and the corresponding economic impact extremely difficult to forecast. In addition to net export effects discussed above, domestic consumption, investment, and government spending are all already being affected by social distancing policies. Government spending may be impacted by the decline in government revenues. If sufficient financing is not available to make up for the revenue loss, then expenditure cuts could become inevitable.

One way to get some idea of the dimension of the issue is to examine the size of the “face-to-face industries.” These industries are not always clearly well-defined, but, for example, consider the following industry shares of GDP in Trinidad and Tobago: administrative and support services (4.6 percent), education (2.6 percent), accommodation and food (1.7 percent), and arts and entertainment (0.2 percent). Together these industries represent 8.6 percent of GDP. Another way of looking at the problem is through employment shares. For example, nearly one-third of workers in Suriname are either in the “services and sales” category or “elementary occupations” category, which include manual tasks like housekeeping, persons who sell off of street carts, and others who are suffering dearly during the social distancing episode. Many people in these professions are among the most vulnerable economically. Social distancing is a domestic factor that is vitally necessary to avoid a human and economic catastrophe, but it comes with its own economic, social, and fiscal costs in the short run.

Finally, there are other idiosyncratic issues in individual countries. Suriname is experiencing great volatility in the foreign exchange market, with international reserves heavily depleted. This is having negative effects on the functioning of the financial system, and all this is mixed with investors’ concerns about the upcoming election. In Guyana, the March 2 election results are still disputed. Finally, natural disaster risks remain relevant for all these countries, and the hurricane season is just around the corner.

A Synchronized Contraction Across Caribbean Countries?

Economists everywhere have expressed concerns about a synchronized recession in large countries. The bottom line is that there is a high probability of a synchronized contraction among the six Caribbean countries, with the likely exception of Guyana. However, even in Guyana, the direct impact of the coronavirus could still play a role, as social distancing is gradually ramped up. In addition, political uncertainty there may eventually take a toll on the local economy.

Policy Options

What can be done? Obviously, the first priority is to “flatten the curve” and contain the coronavirus. Social distancing is of particular importance given the limited number of intensive-care facilities in Caribbean countries. It is critical to keep the human capital stock healthy for when the crisis is over.

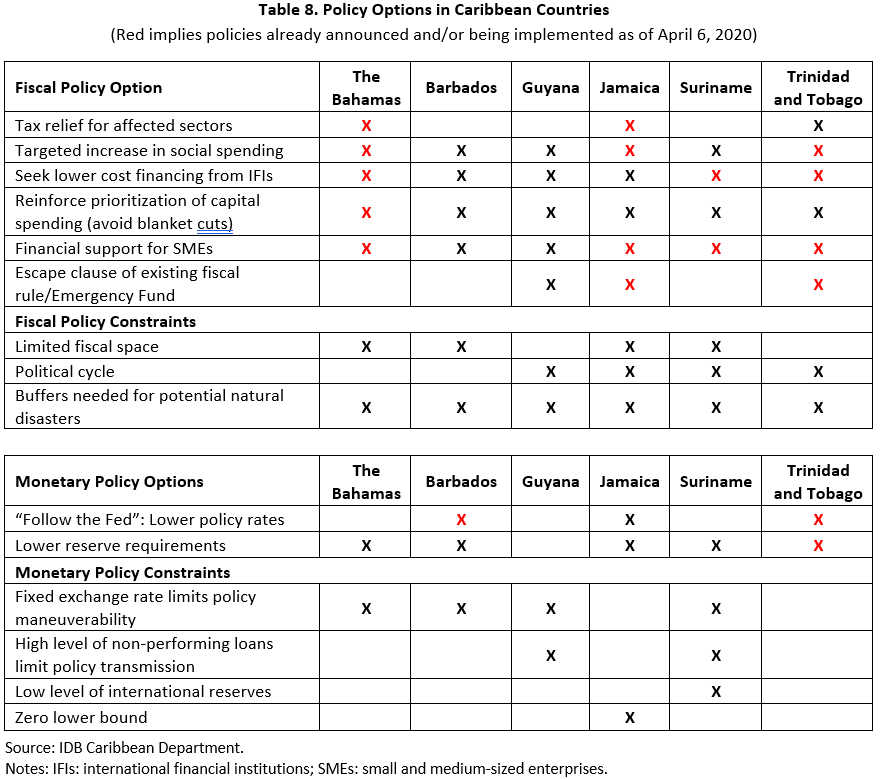

In terms of fiscal, monetary, and social policies, there are numerous actions that have already been announced by the Caribbean governments (Table 8). They range from tax instruments to targeted spending and financial relief for small enterprises. One idea that might be worth considering is to tax the windfall from lower oil prices as a revenue source for targeted support to affected people and businesses. Depending upon the organization of oil imports and the electricity sector, one could either directly tax the imported oil or apply fuel taxes at the pump and tax surcharges on electricity provision.

On the social policy front, one message for policy design, from a macroeconomic perspective, is to make policies both “targeted and temporary.” Given limited fiscal space, escape clauses for the post-crisis phase are critical. On the targeting side, the quality of data is critical. That said, there are proxy means for targeting in cases where data are insufficient for more precise means. For more information on social policy options please see a forthcoming brief from the IDB.8

The Country Summaries below provide information on the policy options and constraints for each country in the face of the COVID-19 outbreak. Each section also summarizes the policy actions already announced or being implemented.

In addition, Table 8 (below) summarizes the macroeconomic policy options and constraints and report on the level of implementation in the Caribbean countries. We will be tracking these policies moving forward and conducting more in-depth analysis that we hope will inform the policy debate. For instance, work is ongoing on tracking the macro impacts of the crisis down to the household level. We are also starting more in-depth work on the design of fiscal and expenditure policies.

Footnotes:

1 The Caribbean region refers to the six member countries of the Inter-American Development Bank that correspond to its Caribbean Country Department: The Bahamas, Barbados, Guyana, Jamaica, Suriname, and Trinidad and Tobago.

2 For an interesting perspective on this issue, see Reinhart (2020).

3 It is true, however, that there has been some variation for individual countries over other periods—for example, a deceleration of recorded arrivals to The Bahamas between 2013 and 2016.

4 For example, the fall in oil prices, if sustained, represents a positive offsetting effect on net oil importers.

5 See the following blog post for results of such an exercise: https://blogs.iadb.org/caribbean-dev-trends/en/covid-19-tourism-based-shock-scenarios-for-caribbean-countries/

6 For a broader discussion of related issues, see Mooney (2018).

7 This indicator derives from a survey of banking sectors conducted by economists from the IDB’s Caribbean Department, based on the World Bank’s 2019 Bank Regulation and Supervision Surveys.

8 The Spanish version is available at: https://www.iadb.org/en/coronavirus/safety-nets-vulnerable-populations.